When examining Nolamba monuments, they are often seen as regional adaptations inspired by central works of the Deccan tradition, including those of the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, as well as the southern Pallava and Chola traditions. Another view holds that Nolamba art incorporates influences from these broader neighboring traditions. A prominent study on Nolamba art cataloging sculptures from Hemavati (Nolamba capital of Andhra Pradesh) in the Madras Government Museum describes Nolamba art as essentially imitating the Chalukya style with some Pallava elements. While identifying a particular specialty or attraction, its specific nature is somewhat undefined.

In exploring Nolamba period art, scholars try to identify its distinctive features by examining the influences of prominent dynasties. Distinctive features in Nolamba sculptures encourage detailed comparative analysis, drawing parallels with late Pallava, early Chola and Rashtrakuta sculptures. The aim is to unravel the origins of the Chalukya, Rashtrakuta, Pallava and Chola elements, shedding light on the sources that contribute to the distinctive features observed in the Hemavati (Madras Museum) sculptures.

The historic region of Nolambavadi was ruled by the Nolamba dynasty from the late 8th to the early 11th century, spanning present-day southeastern Karnataka and adjacent areas. Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are at the maximum. Despite its importance, Nolambavadi has received limited scholarly attention. Why do many historians of Indian art classify antiquities based on binary distinctions, in their pursuit of monuments?

It is essential to question why the adherence to traditional assumptions of central (perceived superior) and binary divisions from major dynastic territories. Residues from other areas such as peripheral (considered less).

For example, a certain hairstyle echoes the Pallava or Chola styles, while a necklace shows signs of Chalukya influence for sure! By comparing Hemavati’s Dakshinamurti with figures from Kaveripakkam, the analysis highlights the influences of the “late Pallavas, heavily influenced by Chalukya Rashtrakuta traditions”. The jatas of the hair show similarities to the Pallava and Chola styles, while the yajnopaveeta (sacred thread) is draped, suggesting the Pallava tradition, but also observed in the Chalukyan territory. These attributes can seem somewhat ambiguous, as styles are often linked to specific dynasties, sometimes to the point of potential meaninglessness.

In scholarly endeavors, there is a prevailing tendency to delve into sources, using them as a tool to discover new perspectives or to understand topics by comparing them with similar ones.

Initially, researchers relied on the time-tested method of tracing artistic origins and influences from prominent dynasties beyond Nolambava to elucidate the genesis or “style” of Nolamba period monuments. However, a thorough examination of the Nolambavadi area requires not only basic documentation, but also a more comprehensive approach to discussing the evolution of art in areas ruled by lesser-explored dynasties.

This suggests a re-evaluation by historians of Indian art of the predominance of ‘essentialism’ in dynastic and regional studies. This ‘essential’ presupposes the existence of a certain ‘spirit’ or ‘nature’ inherent in a dynasty—the artistic essence or characteristic of each dynasty expressed through distinct shapes, images and motifs considered unique to that dynasty.

Such a view allows for an arbitrary definition of artistic essence and assumes that this essence is diffused outward, overriding all other considerations. The problem with this line of thinking is its tendency to posit the defining features of a Chola temple as the absolute essence of ‘Chola’.

Consequently, when similar—though not identical—characteristics are observed elsewhere, it is automatically assumed to be representative of the ‘Chola’ style.

The stronger this perceived essence (as seen in great dynasties), the more widespread the “influence” it exerts on others.

A room designated only for major dynastic figures or prominent styles in the field of artistry seems to relegate all others to dependent styles. Consequently, in scholarly interpretations, art is often reimagined to reflect a contemporary aesthetic reimagining of the regional political hierarchy under consideration. This approach ignores the multifaceted and diverse elements that contribute to the diverse form of the temple.

How should we approach the art that originated in the peripheral regions around the major dynastic centers of India? Should the stylistic characteristics of each local art form automatically be linked to the “essential character” of neighboring macro-centers, or can we gain a deeper understanding by viewing this art primarily as locally rooted and relatively independent? Are the Nolamba monuments merely inferior imitations, produced by their dominant military and political neighbours, or do they represent authentic expressions shaped by their own unique local circumstances?

Proposes that monuments in smaller, less explored areas should not be considered simply as a composite of the “influences” of larger and more recognized dynasties. Rather, they should be recognized as independent local expressions that reveal dialectical interaction with neighboring monuments rather than as a common offering. More precisely, monumental symbols are not responsive to others, but to the human agents responsible for creating them. To understand temple art, it must be seen as the result of human activities, reflecting the interests of those agents, not as hidden essences.

Smaller, “minor” political entities have their own autonomous wills and are distinct from their more influential neighbors. Thus, their manifestations in politics or aesthetics are distinct and not merely scaled-down reproductions of the interests or motives of their nearest neighbors. Although we cannot fully identify all the agencies involved and their motivations, it is essential to remember that the temple is a multifaceted monument both in form and purpose.

In this context, we are seeing center and periphery as a dynamic contrast, rather than as a simple scale in which each increases as the other decreases. An important point to note is that political and artistic centers are not always perfectly aligned, but it is imperative to consider governance and centralization in our discussions.

A crucial but often overlooked point is that what is considered peripheral in relation to the “main” center is central in a different context. In Nolambavadi, considered peripheral by many art historians, it is designated as the center of the Nolamba capital Hemavati. It is essential not to look down on Hemavati and the rest of Nolambavadi’s art as less original. Although monuments are inspired by models in other areas (or “influenced” as we usually say), the final product is shaped by factors such as the skills of the artisans, available materials, patron preferences, and other specific requirements based on immediate observations.

In the following examination of artistic developments in peripheral regions such as medieval and Renaissance Eastern Europe, it is defined as a place distant from a dominant center and open to diverse influences from multiple regions. He emphasized mixing and matching these influences, giving artists in peripheral areas the freedom to independently select and develop elements, thereby creating autonomous and original art.

Appreciating these insights, the delineation of central and peripheral spaces within this perspective appears somewhat consistent. Another point of view, which I think is more applicable to medieval South India, regards the major centers as both independent and interconnected. In a time characterized by slow and restricted communication, all centers, regardless of their importance, are peripheral in relation to each other. They interact and react as needed, drawing from various influences. Artists away from the main dynastic centers were exposed to different forms from different regions. They make these designs subject to the limitations of their training and abilities, to meet specific needs without being tied to any particular tradition but open to influences from neighboring sources. When building temples, multiple agents are involved at different stages, contributing to the final appearance. Although local traditions and autonomy are important, they do not preclude the potential use of other elements.

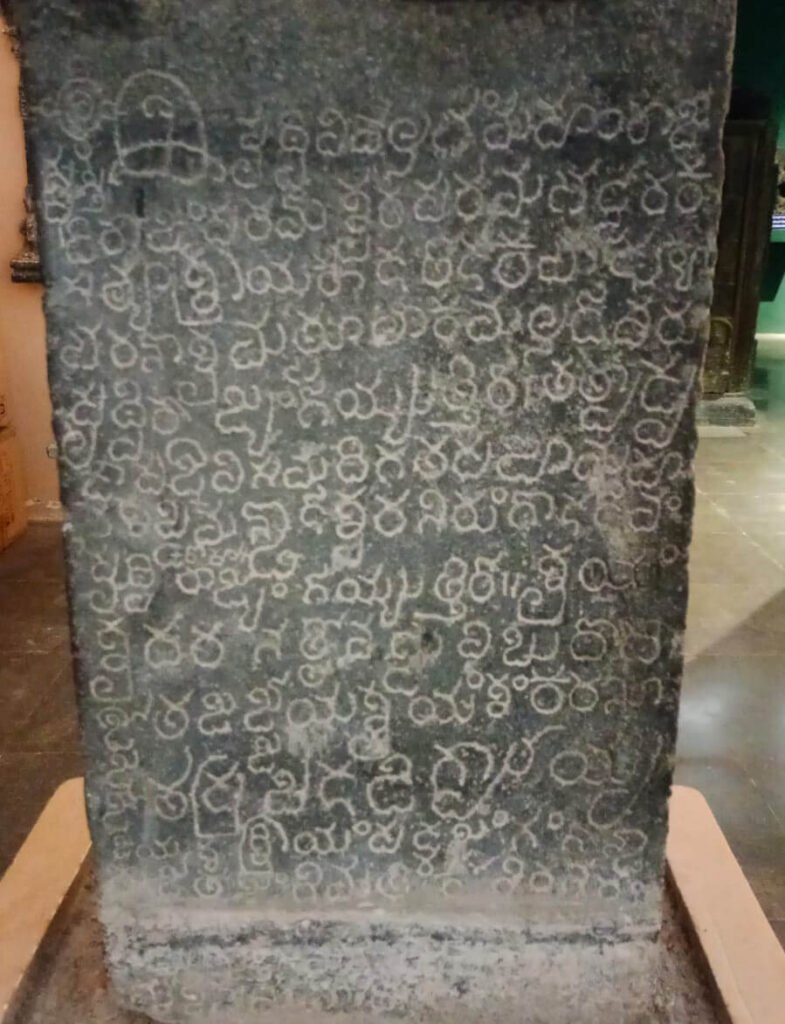

Ancient inscriptions of Nolambaraju were found at Cholemarri

Mynaswamy, a historian who compiled a Telugu inscription near Cholemarri village in Roddam mandal, said.Historian Mainaswamy reported that a Telugu inscription dating back to the Vijayanagara Empire was found in the fields near Cholemarri village of Roddam Mandal. In this inscription there are idols of Veeragallu, Shivlingam and Nandi.

With the help of local villagers, Mainaswamy located the royal inscription of Mahendra Nolambadi, who ruled from the capital of Henjeru (Hemavati) in the fields east of Cholemarri.To the west of the village, there are additional inscriptions and sculptures of the Nolambuls and Vijayanagara viragallu, in coherent Kannada characters. Essentially, the inscription stone is partially sunk into the ground.

Mainaswamy suggested that more historical features can be discovered if archaeological excavations are carried out in the surrounding areas of Cholemarri.